Rescue Groups

Catholic Church

The Protestant Church

The Voluntary Ambulance Service

The Committee for the Aid of Jewish Refugees from Northern Transylvania

The Hashomer Hatzair

The He Halutz Youth (Zionist Pioneers)

Institute of Geology, Budapest

Zionist Youth

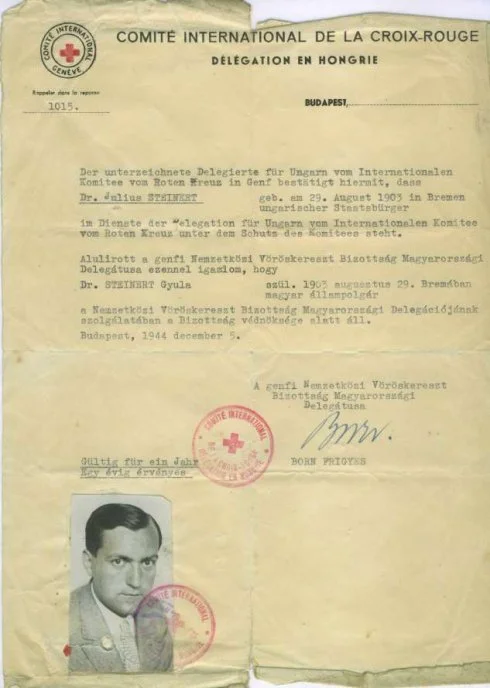

Clothes-Collecting Company (Ruhagyujto Munkasszazad), known as Section T of the International Red Cross

The International Red Cross

Good Shapard Committee

The Jewish Agency for Palestine

The Jewish Council (Zsido Tanacs) Budapest

The Refugee Aid Committee (Comisia Autonoma de Ajutorare)

Relief and Rescue Committee of Budapest (Va’adat ha-Ezra ve-ha-Hatsala be-Budapest; Va’ada)

Ujvary Group

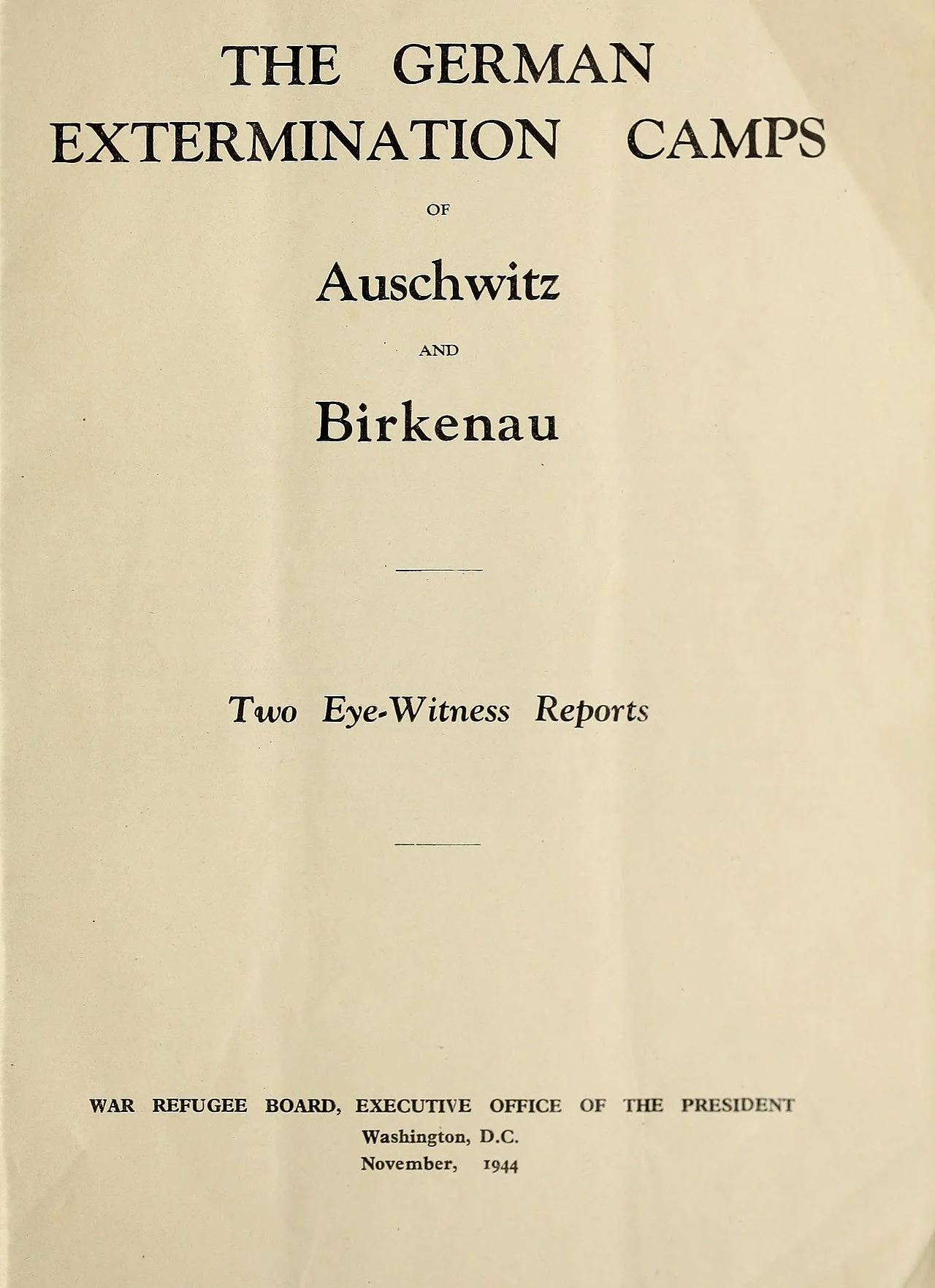

War Refugee Board, US Department of the Treasury, 1943-45

The Working Group, Slovakia

Catholic Church

Lévai 1948 pp. 394-:

“On December 23rd Gabor Vajna, the Minister of the Interior, issued a decree ordering all Jews hiding in the town to move into the ghetto voluntarily. Some ten thousand were affected by this decree. Some of them were hiding in Catholic and Calvinist ecclesiastic institutes and others were being sheltered by Christians. The Catholic institutions particularly were foremost in offering shelter to the baptized Jews as well as to the Jews who still clung to their faith. Here are some illustrating examples:

“The Lazarist Fathers sheltered some 30 men in their prayer house, all of whom escaped. In the house of the Sisters of Mercy 150 children and 50 adults found refuge. The children were all off-springs of deported parents and no notice was taken of their confession. The gates of the religious houses were opened only to poor and forlorn creatures; those offering money could not count on help. The Nyilas repeatedly expressed a desire to search these houses, but miraculously they were always satisfied with looking through some papers in the porter's lodge, therefore all refugees were saved. The Sophianum hid 80 women, 40 children and-later on-10 men. All refugees were saved thanks to the energetic conduct of the Mothers. The Oblatas of the Benedictines saved 10 political refugees and 82 Jews. 110 were hiding in the Sion Convent on the Svabhegy. They were discovered by the Gestapo, but the nuns succeeded in smuggling them out and offering them shelter elsewhere, so that all of them were saved. The Franciscan Missionary Sisters offered refuge to 120 children and 30 adults. Here the Nyilas carried out a raid and dragged away most of the refugees. The nuns were robbed of all their possessions. Under the pretext of illness 100 Jews were sheltered so cleverly in the hospital of the nuns of St. Elisabeth that they were not discovered in spite of the frequent searches conducted by the Nyilas. The Society of the girls of Sacre Coeur hid refugees on the premises of their bookshop. They assisted about 2,000 Jews in obtaining false papers and accomodation.’’

“One hundred girls of Jewish origin found board and lodging in the Regnum Marianum; all of them were rescued. The College of St. Anne was hiding about 150 persecuted people, most of them provincial refugees. Benevolent policemen successfully guarded the college against the Nyilas. 30 refugees found shelter in the Collegium Theresianum. The Nyilas searched the house three times, but met with no success, as their intended victims were able to reach the neighbouring houses through a corridor hidden (395) in a bomb-damaged corner of the building. All of them survived. The "Champagnat" Institute of the Order of Mary had 100 pupils as boarders, together with 50 adults, the parents of the children. An agent provocateur, (an SS. man from Alsace), who pretended to be a French soldier in hiding, denounced the monks. As a result they suddenly found themselves, one night, surrounded by 40 members of the Gestapo, who dragged six monks, two thirds of the children and most of the adults away. The monks, after having undergone terrible tortures, were taken to the fortress and released, but the Jews were all killed. The few adults and children left in the institute were miraculously saved. In the house of the Sisters of the Divine Saviour 150 children found refuge, but the Nyilas and the Gestapo, who were accomodated in the neighbourhood, found them and dragged them away. The Nyilas took them to their headquarters in Ujpest, from where they drove 62 into the Danube at Meder Street. These were killed, the rest deported. The "English Sisters," in two of their houses, gave refuge to 100 children and 40 adults, all of whom were saved in spite of the molestations of the Nyilas. Temporary shelter for 15-20 children was available at the Central Seminary. The "Hospitalors" of Óbuda sheltered 25 adults and 15 children, but were discovered by the Nyilas; it was, however, possible to transfer them to Pest, where they were placed in protected houses. The Convent of the Good Shepherd hid 112 girls, which twice escaped the clutches of the Nyilas by hiding in neighbouring houses whilst the convent was being searched. 150 refugees were hidden in the Jesuit College. The Prior, Father Jacob Raile, was one of the chief executives of the rescue actions. His name became legendary in Budapest. All day long he used to pull strings in the town, procuring false certificates of baptism for his proteges, the number of which increased at the rate of at least one or two a day. The rescue action of the Jesuits became so far-famed that hardly a day passed on which their house was not searched by the Nyilas. Father Raile put an end to these molestations by dressing some of the 100 Christian deserters in hiding in police uniforms and making a "police station" out of the porter's lodge. From that day onwards no Nyilas man passed their threshold. Father Reisz and particularly Father Joszef Janossy took a prominent part in the rescue action. The latter was the leader of the Holy Cross Society, which had taken charge of the rescue action of the baptized Jews. The Ranolder Institute established a "faked war industry plant" employing 100 Jewish girls. The Order of Divine Love hid 110 refugees. Unfortunately they were discovered by the Nyilas, who were billeted on the other side of the road; they attacked the Convent and dragged away and killed all refugees with the exception of five who managed to escape through the roof. 25 refugees hid in the home of the Social Sisters. They were denounced by an employee, a Nyilas (396) sympathizer. Surprisingly the Nyilas recognised all documents with the exception of those of six of the refugees, who, together with Sister Sarah Schalkahazy and Vilma Berkovits, were dragged away and murdered that same day. Safe-conducts and forged legitimations were distributed on a large scale by the Institute of St. Teresa and the refugees provided with these were placed in private houses by the Sisters. 30 found refuge in the institute itself. 26 were hiding in the home of the Catholic Youth, who also issued several hundred safe-conducts and false legitimations. Although a German Motorised Division was billeted in the home, the Jews, living on a separate floor, were able to escape. In the Home of the Sisters of Mercy of Szatmar 20 Jews were hidden, and although the inhabitants of the house-the home being part of a large tenement building-knew that the Sisters were hiding Jews, all were saved. In the Convent of Sacre Coeur 200 women and children survived the siege. 11 refugees were hidden in the small premises of the Charite. One night the manager was arrested, cross-examined and threatened. Nevertheless he did not betray his proteges, who were all saved. The Josephinum (Society of the Virgin Mary) in the very neighbourhood of the Nyilas headquarters successfully hid 60 children and two adults. 20 persons found refuge in the small hospital of the Sisters of the Eucharistic Union. They were discovered and taken away by the Nyilas, who tortured the Prioress, but finally let her off with the warning that they would kill her, if they ever caught her hiding Jews again. After her escape the Prioress immediately rented a flat-Prelate Dr. Arnold Pataky placed his own flat consisting of four rooms at her disposal-and again gathered around her large numbers of persecuted Jews. The Fathers of St. Salese gave shelter to 12 adults and 40 children. Three times the house was broken into, always in the middle of the night. On the first occasion all hidden men were taken away, whose legitimations were found to be dubious. All of them were shot. The same fate awaited the five men, who were dragged away on the second occasion. On Christmas Eve, the third occasion, 13 small boys were carried away. 12 of them were shot on the shores of the Danube, the thirteenth managed to escape by jumping into the icy river and dodging the bullets sent after him. The Prior and his deputy were taken to the Nyilas headquarters and severely beaten. Only the intervention of the Nuntio saved their lives. The Nyilas looted the seat of the Order and carried off the contents of the cash box.’’

In the air-raid shelter of the Order of St. Benedict, 80 persecuted Jews survived the siege. 15 others were successfully concealed in the monastery of the Cistercian Order, whilst the Carmelite Sisters accorded hospitality to 300 children.’’

The Protestant Church

Levai 1948 p. 398:

“Special mention must be made of the rescue activities of the Scottish Mission. Following the "Anschluss" of Austria, the refugees found a helping hand here. Their ministers: George (397) Knight, Gyula Forgacs and Dr. Lajos Nagybaczoni Nagy, fearlessly branded racial ideology in their sermons and lectures as being contrary to all Christian ideals. Jewish artists and writers, who, as a result of the Jewish laws, were forbidden to appear in public, were given an opportunity to express themselves in the "cultural gatherings" arranged by the Mission.’’

“After the German forces had entered Hungary the Gestapo carried away Miss J. [Jane] M. Raining, the heroic head of the Girl's School. She was arrested on April 25th, 1944. The Scottish lady first showed her personal documents and then produced the safe-conduct of the Swiss Legation, which the Germans brushed aside with a wave of the hand. She was not allowed to take her Bible with her, although she repeatedly asked to be permitted to do so. The Swiss Legation and the Calvinist Church did their utmost to obtain her release. Bishop Ravasz intervened with Sztojay and Horthy, but was unsuccessful, although the Hungarian Government intervened on other occasions. Then on August 22nd a Gestapo man appeared at the Scottish Mission with a bundle of papers, the legacy of Miss Raining, and reported that she had died in Auschwitz, where she had been deported to. Miss Lee, who was imprisoned together with Miss Raining, later reported that she had twice been taken to be cross-examined. She was accused of: 1) working among Jews, 2) crying on first seeing the Jewish Star on her Jewish pupils, 3) dismissing her Aryan housekeeper and engaging a Jewish one instead, 4) listening to the news broadcasts of the British Broadcasting Corporation, 5) receiving many English visitors, 6) talking politics, 7) visiting British prisoners-of-war, 8) sending them parcels.’’

“Miss Raining courageously admitted these "crimes," with the exception of No. 6. With that her fate was sealed.’’

The Scottish minister, George Knight, was called home in 1940, Gyula Forgacs died in 1942 and therefore the remaining minister, Lajos Nagybaczoni-Nagy was left in sole charge of the rescue action during the difficult times of the Szálasi Regime. The Mission inaugurated a Children's Home under the protection of the Swiss Red Cross, where 70 children, 30 mothers and 10 fathers, all of them Jews, found shelter. Zoltan Tildy with his family, Ferenc Nagy and Victor Csornoky were also hiding here. On December 12th, 1944, police came to the house in order to escort the Jews hiding there to the ghetto. Nagy succeeded in rescuing some of the persecuted, whereas the rest were taken into the ghetto. There, on behalf of the Mission, the visiting minister and his assistants provided them with food, until, with the help of faked documents, it was possible to smuggle them out of the ghetto and to bring them back to the Mission again, where for the future they remained unmolested.’’

“The rescue of the Jews in hiding was greatly facilitated by the false legitimations produced by some clever groups; in most cases they were brought into circulation unselfishly and without (398) payment being demanded for them. Two groups, who carried on this work on a large scale deserve mention. Generally these actions were started in connection with the resistance movement against the Germans, although others had already existed before the German invasion, whose aim it had been - as an anti-Fascist movement - to hide English, Dutch, French, Belgian and Polish officers and men who had escaped from German prisons and to provide them with material help and personal documents. After the German invasion, partly for political and partly for racial reasons, the rescue of the persecuted became predominant and these groups with their organisation were of the greatest help to the Jewish rescue actions. Without exception the members of these groups were Christians with Left-wing sympathies. One of these groups for instance was led by: Dr. Tibor Szalay, director of the Institute of Geology and his wife, Laszlo Csuros, Rafael Ruppert, Ferenc Korom, Karoly Dobos, a Calvinist minister, Baron Jeno Josika and others. They were greatly assisted in the production of forged documents by "underground" foreigners: Capt. Roy Natush from New Zealand, the British Lieutenant Thomas Clement, Flight-Lieutenant of the R. A. F. Reginald Barratt, Sergeant Tibor Weinstein of the Palestine Regiment, the British Privates Gordon Tasker and R. W. Jones, Gordon Park, and Heburn and the Dutch Lieutenants G. van der Waals and W. Puckel.’’

The Voluntary Ambulance Service

Levai 1948 p. 378-379:

THE AMBULANCE SERVICE AS RESCUERS OF THE JEWS.

“By request of the Jewish Council, the Ambulance Service placed two of their largest trucks with trailers at the disposal of the ghetto Jews and from November 15th onwards answered about 70 to 80 calls per day. In faithful execution of their duty the Ambulance Service never discriminated between races and religions; on the contrary, it can be stated that cases occurred in which they gave first aid to people in the street although they wore the Star of David - this was contrary to a decree then in force - and carried them away after having bandaged them, in order to accord them further protection.

“The Nyilas strictly forbade the Ambulance Service to attend to Jews. It was only possible to put the two abovementioned ambulances at the disposal of the Jewish Council by selling them, together with 13 other cars, to the Swedish Legation for the sum of 1 Swedish Crown on November 18th. (It is interesting to note that the Nyilas Lord-Mayor and Mayor of Budapest consented to this transaction taking place.)

“With the consent of Dr. László Bisits, Chief Medical Officer, the ambulances, accompanied by Wallenberg, went as far afield as Hegyeshalom and brought back some Swedish-protected deportees, who were in a very sorry condition indeed. Dr. Bisits went to Balf-Spa to bring back 15 Jews in possession of Portuguese passports. The ambulances - despite the orders to the contrary - were also available for taking sick Jews to hospital or for bringing them back after recovery. The Voluntary Ambulance Society of Budapest had, taking everything into consideration, no small share in the rescue actions.

“On December 3rd Nyilas men attacked the Jewish settlement of the International Red Cross in Columbus Street. At first some 5 to 600 Jewish emigrants occupied the camp consisting of an old cottage and an improvised barracks at the back of the Deaf and- Dumb Institute. Later on the number rose to 1,600 as refugees from Kolozsvar, Nagyvarad, Szeged and so on flowed in, who found it impossible to find some other shelter in Budapest. The camp was originally guarded by the Germans, but the "Sonderkommando" left at the end of August.’’

“After the events of October 15th, the number of the occupants of the camp rose enormously. 3,600 men crowded into a space sufficient for perhaps 180, sleeping practically on top of each other and in shifts. There was no question of sanitary measures and as a result epidemics raved.’’ (379)

“At 2.30 p.m. on the afore-mentioned 3rd of December the ambulance was called to Columbus Street. They were refused admittance to the camp; Acting Police Constable No. 2565, who had sent for them, reported that shots had been fired in the camp and that there were a number of fatal casualties. The door was just opening and somebody ran out, leaving a bloody trail behind him. Close on his heals were a couple of Nyilas men, who again fired at the escaping Jew. The victim collapsed just in front of the doctor accompanying the ambulance: one of the shots had proved fatal. The victim turned out to be the deaf and dumb Moses Roth, aged 16.’’

“In the ghetto the transports were being formed. In the meantime the young doctor succeeded in rescuing two young men, both profusely bleeding from shot wounds: Endre Gross, aged 21, joiner, and Mano Wertheimer, aged 17, shop-assistant. Much determination was needed to protect them, as the Nyilas men wanted to shoot them whilst they were still being bandaged. This was the 26th case in the log-book entries of the Ambulance Service for that day, and it closed with the remark: The ambulance had to leave without the accompanying doctor having been able to effect an entry into the camp. The Camp Eldest, together with his family and some other men - in all 9 persons - were assassinated by the Nyilas. Amidst bloody scenes those within the age-limit were driven into the ghetto, the others to Teleki Square and from there to Bergen-Belsen.’’

“At 2 a. m. on December 4th the was ambulance again called out. They discovered that, starting from the corner of Alfoldi and Fiumei Streets, along the whole of Nepsinhaz Street up to the corner of Jozsef Boulevard, the corpses of members of the Jewish Labour Companies had been thrown out of the back of a truck. They were beyond help, all of them had been killed by shots through the back of the neck. (Log-Book of the Ambulance Service, item 3-9.)’’ (380)

The Committee for the Aid of Jewish Refugees from Northern Transylvania

‘’The Committee for the Aid of Jewish Refugees from Northern Transylvania was created in Bucharest, Romania, under the Zionist Aliyah office. It was headed by Ernö (Ernest) Marton, a former newspaper editor and a former member of the Romanian parliament. This organization helped hundreds of refugees flee to safety. Prominent members of the committee were Martin Hirsch, J. Schmetterer, Leon Goldenberg, Paul Benedek and D. Lampel.’’

The committee also worked with leaders of Romanian Jewry Abraham Zissu and Wilhelm Filderman.

[Braham, Randolph L. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), pp. 907-909, Lévai, Jenö. Black Book on the Martyrdom of Hungarian Jewry Central European Times Publishing, 1948, Vago, Bela. “Political and Diplomatic Activities for the Rescue of the Jews of Northern Transylvania.” Yad Vashem Studies, 6 (1967), pp. 155-174.]

The Hashomer Hatzair

“The Hashomer Hatzair was a prominent rescue organization that operated in Budapest after the Nazi occupation. Like the other youth groups, members impersonated Nazi and Arrow Cross soldiers and carried Aryan papers. Moshe Rosenberg was a prominent leader. The Hashomer established a Haganah committee with Moshe Pil, Menachem (Meno) Klein, Leon Blatt and Dov Avramcsik. The Hashomer Hatzair distributed protective papers and documents in Budapest.’’

[Braham, Randolph L. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), pp. 999-1000, Lévai, Jenö. Black Book on the Martyrdom of Hungarian Jewry Central European Times Publishing, 1948]

Glass House on Vadasz Street

The He Halutz Youth (Zionist Pioneers)

The He Halutz Youth (Zionist Pioneers) was a militant rescue organization of young Jews in Budapest. There were approximately 500 active members of the Halutz. Their rescue operations in Budapest in 1944-1945 were an important part of the overall rescue of Jews in the Hungarian capital. Before the Nazi occupation, the Halutz provided Polish, Slovakian and other refugees in Hungary with false identification papers. They worked with both the Va’ada and the Tiyyul (Excursion) departments. After the German occupation, they continued to distribute counterfeit identification papers. Members of this operation included Dan Zimmerman, Saraga Weil, Sandor Groszmann and Efra Teichmann. Many of the Halutz members operated underground, sometimes even passing themselves off as members of the SS or the Arrow Cross. The activities of the Halutz were headquartered in the building of the Jewish Council. Halutz members Jenö Kolb and Yehuda Weisz were also part of the Jewish Council’s Information Section. Kolb and Weisz distributed Jewish Council certificates to a number of Jews who were smuggled to Budapest from ghettoes in the provinces. In July 1944, the Halutz made their headquarters at the Glass House on Vadász Street. Halutz leaders became workers at the Glass House. In the Glass House, they continued illegal rescue programs with Tiyyul. Halutz members distributed a number of Swiss protective papers. After the Arrow Cross takeover, Halutz obtained guns and built fortified bunkers throughout Budapest. Jews were hidden and housed in some of these bunkers. In the fall of 1944, Halutz continued to mass produce counterfeit protective passes that were being issued by neutral diplomats. Wearing the uniforms of the Arrow Cross, the SS and other military units, the Halutz rescued Jews from captivity. They rescued their fellow Jews from yellow star houses, internment camps and the Obuda (North Buda) brickyard. They liberated Jews from prisons and from Arrow Cross execution gangs on the Danube. Halutzim also worked with Department A of the International Red Cross, led by Otto Komoly. With Department A, they helped supply food to children’s homes and the protected houses. Other prominent members of He Halutz were Zvi Goldfarb, Rafi (Friedl) Ben-Shalom, Peretz Revesz, David (Gur) Grosz, Sándor (Alexander; Ben Eretz) Groszmann, Yitzhak (Mimish) Horváth, József Mayer, Moshe (Alpan) Pil, Moshe Rosenberg and Efra (Agmon) Teichmann.

Braham 1981 pp. 1319-1332:

“The Rescue Activities of the Hehalutz Youth. In contrast to the positions taken by the Central Jewish Council (see Chapter 14) and the Vaada, the members of the young Zionist pioneers (and there were only a few hundred of them) took militant action for the rescuing of Jews. By doing so they were responsible for what were by far the brightest hours in the tragic wartime history of Hungarian Jewry. They never engaged in open combat and they failed to sabotage any of the many rail lines leading to Auschwitz (they did not have this kind of power), but their heroic rescue operations can clearly be classified as acts of resistance.’’ (1319)

“The movement was under the leadership of young Zionists belonging primarily to the Hashomer Hatzair and Dror groups. The dominant role in the movement was played by young Polish and Slovak refugees who came to Hungary in 1942-1944. Among these were Neshka and Zvi Goldfarb of Poland, and Rafi (Friedl) Ben-Shalom and Peretz Revesz of Slovakia. 247 These were soon joined by a number of equally brave young Hungarian Halutzim, who distinguished themselves during the underground struggle. Special mention must be made of the heroic activities of David (Gur) Grosz, Sandor (Alexander; Ben Eretz) Grosszmann, Yitzhak (Mimish) Horvath, Jozsef Mayer, Moshe (Alpan) Pil, Moshe Rosenberg, and Efra (Agmon) Teichmann.’’ 248

“With approximately 500 members in Budapest, the leaders of the Hehalutz concentrated their attention on rescuing individuals, mostly their comrades and Zionist sympathizers; they had become convinced that there was no hope for the Jewish masses. 249 The nature and scope of their activities varied with the changing situation. Before the occupation, the Hehalutz was primarily engaged in the rescue and "legalization" of refugees. They provided these refugees with the necessary-mostly Aryan-identification papers, and rescued a number of Jews from Polish, Slovak, and other camps. In this rescue campaign they worked closely with the Vaada, especially its Tiyul section.’’ 250

“Cooperation between the Hehalutz leaders and the Hungarian Jewish establishment and Zionist leaders was not always smooth or easy. The Slovak and Polish Hehalutz and refugee leaders were particularly scornful about the official leadership of Hungarian Jewry. Their assessment was largely shared by Gisi Fleischmann and other leaders of the Bratislava Vaada. Ben-Shalom identified Hungarian Jewry "as a particularly ugly lot" that did not want to know anything about events in the neighboring countries, although he and his fellow refugees were doing everything possible to enlighten them.’’ 251

“The Hehalutz youth as a whole did not get along with the Hungarian Zionist establishment either. Ideological differences were compounded by generational conflicts. The older, traditional leaders of the weak Hungarian Zionist movement (the so-called Vatikim) resented what they perceived as the intrusion, impatience, and militancy of the younger pioneers. The latter, in turn, became increasingly and ever more vocally scornful of the establishment leaders’ complacency and (1320) bureaucratic tendencies. While they questioned some aspects of the Vaada leadership, their ire was directed especially against Krausz, the Mizrachi leader, for his allegedly improper and incompetent administration of the Palestine Office. 252 The dispute erupted into open conflict during the Nyilas era (see below).’’

“Just before the occupation, the Hashomer Hatzair group decided to have all its members " aryanized" in order to assure their freedom of movement. While extremely risky, this enabled them to carry out their rescue operations more effectively. Under the leadership of Moshe Rosenberg they also established a Hagana Committee (composed of Pil, Menachem (Meno) Klein, Leon Blatt, and Dov Avramcsik) which, however, was short-lived.’’

“The German occupation of Hungary caught most of the Halutzim off guard. Their immediate concern was to assure, first and foremost, their own and their families’ safety. Because of the speed with which the anti-Jewish measures had been enacted in the countryside and the weaknesses of the Zionist movement there, the young Halutzim decided to focus on their rescue activities in Budapest. During the first phase of the occupation, the Hehalutz concentrated its attention on the production and distribution of forged Aryan identification papers-including even Gestapo, SS, and Nyilas membership cards. 253 For reasons of security, the leaders in charge of this aspect of the underground operations, including Dan Zimmermann, Sraga Weil, Grosz, and Teichmann, had to shift their headquarters at great risk to themselves. They naturally never wore the Yellow Star badge, which to their great consternation caused some establishment Jewish leaders to accuse them of trying to extricate themselves from the common lot. Presumably unaware of the ominous implications of the badge, some among the latter were in fact urging their fellow Jews to wear the Yellow Star in proud defiance.’’ 254

“Another important aspect of the Hehalutz work during this period was the organization of small groups of young men and women, mostly followers of one or another Zionist organization, for the smuggling of Jews into Romania and Slovakia, where the anti-Jewish drive at the time was at a standstill. Among those most active in the smuggling of Jews into Romania were As her Aranyi and Hannah Ganz (Grunfeld), members of Dror-Habonim movement. According to their postwar accounts, they were unable to persuade the establishment leaders of the Jewish (1321) communities they bad contacted in Northern Transylvania about the seriousness of the situation. Nevertheless, they managed to distribute a number of forged documents and smuggle a number of Jews across the Romanian border, including Rabbi Mozes Weinberger, the Chief Rabbi of the small Neolog community of Kolozsvar. 255 A few groups of Jews were also smuggled into Tito's Yugoslavia. After the capture of one of their comrades (Avri Lisszauer), this route was de-emphasized, especially since the Vaada leaders had protested that its use was a threat to their negotiations with the Germans.’’ 256

“Interestingly, while the Hehalutz leaders questioned some of the activities of the Vaada, they too failed to engage in the large-scale distribution of the Auschwitz Reports, which might have had a greater impact on the provincial Jewish leaders and masses than the warnings by the young Zionist emissaries. 257 Moreover, in spite of their conflicts with the Vaada, the Hehalutz leaders tried to make sure that as many of their own followers as possible were included in the Kasztner group. And in fact on the night of June 30, when the transport left Budapest, a large number of the Halutzim managed to "illegally" climb onto the train.’’

“Much of the illegal work of the Hehalutz was directed from the headquarters of the Central Jewish Council, where the masses of people seeking help or inclusion in the Kasztner group gave them cover and allowed them to operate unobtrusively. Some of their comrades, including Jeno Kolb and Yehuda Weisz, who were associated with the Council's Information Section, had given them forged Council certificates through which a number of Jews were brought to Budapest from the provincial ghettos. Also active toward this end was the so-called Provincial Department (Videki Osztaly) of the Council, which was headed by senior Zionists, including Lajos Gottesman of the Betar and Moshe Rosenberg of the Hashomer Hatzair movements. In the relative calm that returned to Council headquarters following the departure of the Kasztner group and the subsequent halting of the deportations, a conflict erupted between the official leaders and the Hehalutz. The latter's operations had become more and more conspicuous, causing considerable consternation among the establishment leaders. Particularly vitriolic was the reaction of the leaders of the Jewish Combatants' League (Zsido Frontharcos Szovetseg), many of whose members had enjoyed exemption from the anti-Jewish laws. The Hehalutz leaders, following (1322) a heated altercation that even led to violence, moved out of the Council headquarters and continued to conduct their affairs from various public parks.’’ 258

“After the Swiss-sponsored Glass House was established late in July, the Hehalutz gradually shifted their headquarters there. The Hehalutz leaders became staff members of the Glass House with considerable privileges, including virtual immunity. They exploited this haven to continue their " illegal" rescue operations-the organization of Tiyul groups as well as the production of forged documents, especially Swiss protective passes. This led to a conflict with the official Zionist leaders of the Glass House, above all Krausz and Arthur Weisz, the owner and chief administrator of the building. 259 The latter were eager not only to safeguard the emigration scheme for which the Glass House operation was launched in the first place, but also to scrupulously uphold all the conditions under which the Swiss bad agreed to cooperate. They were also concerned about their own welfare after Magyar Szo (Hungarian Word) published an expose on the Glass House. The dispute became so intense that on September 5, Krausz and Weisz allegedly threatened to call the police to forcibly evict Pil and Teichmann. A similar incident involved Rafi Ben-Shalom on October 15.’’ 260

“Although the relationship between Krausz and the Hehalutz leaders remained tense, the latter continued to use the Glass House as the center of their operations. The relationship worsened after the Nyilas coup, when the Glass House became the refuge of close to 2,000 Jews. 261 To some extent, this was because the crowds that milled around daily included informers and occasionally even detectives, whose activities contributed to the misunderstanding and tension between the Jewish groups.’’

“During the Nyilas era, the Hehalutz stepped up their daring efforts. Some of the young pioneers managed to acquire guns by taking advantage of the chaotic conditions on the day of the coup. Others, especially those associated with the Dror, led by Goldfarb and other Polish refugees, 262 built bunkers in various parts of the capital. Seven or eight bunkers were built; there is no information as to the number of Jews who were actually saved in them. The one built on Hungaria Boulevard was discovered by the Nyilas and in an exchange of fire there were casualties on both sides.’’ (1323)

“The production and distribution of forged papers took on a new dimension. In addition to continuing the forging of Aryan papers, the Hehalutz intensified the mass production of protective passes (Vedolevelek; Schutzpässe) and related documents that were issued by the representatives of the Vatican and the neutral states; especially valuable were copies of papers issued by the Swiss and Swedish authorities (Figures 29.4-29.11). They also reproduced all the stamps and seals used by these authorities as well as those used by the Hungarians and the Germans. (One of the stamps inadvertently led to the arrest of a number of people because it misspelled the word " Suisse" as " Susse.")’’

“Perhaps the most heroic actions undertaken by the Hehalutz involved the rescue of Jews from the hands of the Nyilas. Dressed in the uniforms of the Nyilas, Honved, Levente, KISKA (Kisegito Katonai Alakulat; Auxiliary Military Unit), and even of the SS, and in possession of guns and automatic weapons as well as all the appropriate orders and documents, they rescued Jews from the locked Yellow-Star houses, internment camps, and the Óbuda brickyard. They also snatched condemned Jews from prisons and even from columns being driven by the Nyilas gangs for execution along the banks of the Danube. It was in this manner that Goldfarb and Grosz were themselves rescued after their capture in December.’’

“In cooperation with the International Red Cross (especially Komoly's Department A, with which some of the members were directly associated), the Halutzim also undertook to help supply food to the many children' s homes, to the so-called "protected houses," and to the ghetto, and to protect the warehouses with food stockpiles. One of the largest of these warehouses was in the Swiss building at 17 Wekerle Sandor Street, which was under the command of Sandor Groszman. 263 The Halutzim had used the buildings assigned to Department A as additional centers of operation. Many of their activities were helped by the mutually rewarding contacts they bad established with several Hungarian officials eager to acquire alibis just before the end of the war. Among these were Andras Szentandrassy, the commander of the camp at the Óbuda brickyard, and Captain Laszlo (Leo) Lulay, Ferenczy's deputy. Contact with the latter was occasionally maintained through Vera Gorog, the daughter of Frigyes Gorog, who was then associated with the International Red Cross.’’ 264 (1332)

“During the Soviet siege of the capital, Nyilas gangs tried a number of times to invade the Glass House in search of food and in pursuit of their murderous aims. Sometimes they were talked into leaving peacefully; at other times, however, they shot into the crowds within the courtyard. In one of these forays they killed four Jews, including the mother of Sandor Scheiber, the postwar head of the National Rabbinical Institute. Among the Vadasz Street victims were also Arthur Weisz, who was taken away through a ruse by First Lieutenant Pal Fabry and never returned, and Simcha Hunwald (alias Janos Klihne) who was shot on January 6, 1945.265 In pursuit of their objectives, the Hehalutz members also maintained contact with the small and loosely organized non-Jewish resistance organizations. The Hehalutz provided these organizations with whatever identification papers they requested; they in tum provided the Hehalutz members with arms and occasional shelter. Among the units with which the Hehalutz cooperated was a POW group headed by a Dutch officer named Van der Walles (or Van-der-Vas) which consisted primarily of Dutch and British officers who bad escaped from German camps. (It was through this group that the Hehalutz rescued Joel Nussbecher.) It also maintained contact with a communist underground group headed by Pal Demeny, and with some anti-German military and bourgeois groups represented by First Lieutenant Ivan Kadar and an officer named Fabry, respectively. 266 Unfortunately the non-Jewish resistance organizations were not very effective; this was a major factor that limited the scope and character of the Hehalutz operations as well. Another negative factor was the passivity of the general population, which in tum was largely influenced by the attitude of the Christian churches.’’ 267

“The Swiss Legation in Budapest under consul, Carl Lutz, pioneered the innovative use of creating protective letters for Hungarian Jews and other refugees in Budapest. These protective papers guaranteed that the bearer of the pass was under the protection of the Swiss government. Lutz employed more than 400 Jewish volunteers as part of a network of distribution. Many of these volunteers were prominent Jews, including Arthur Weisz, who was the owner of the famous Glass House on Vadasz Street. Other Jewish Halutz volunteers who worked with the Carl Lutz were Arthur Weisz, Mihály Salomon, Alexander (Sanyi) Grossman, Eliyahu Gellert (Gal-Or), Dr. Alexander (Sándor) Nathan and Simcha Hunwald.’’

Notes

248. Vago, " The British Government and the Fate of Hungarian Jewry," p. 217.

249. For a view of the photograph, see Th e New York Tim es, February 24, 1979.

250. One of the Jewish leaders (Leon A. Kubowitzki) had opposed the bombing of Auschwitz, fearing that the first victims would be the Jewish inmates. He suggested instead that "the Soviet government be approached with the request that it should dispatch groups of paratroopers to seize the buildings, to annihilate the squads of murderers, and to free the unfortunate inmates." See his letter addressed to Pehle on July 1, 1944, and Yad Vashem Archives M-2/H-I 8. See also Dina Porat, The Blue and the Yellow Stars of David. The Zionist leadership in Pales tine and the Holocaust, 1939- 1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), pp. 212-220. There is no evidence that either the Hungarians or the Germans ever went along with Krausz's interpretation that the 7,000 certificates-were for entire families.

252. Both letters can be found in the Pazner files in the archives of Yad Vashem.

253. Summary Report of the Activities of the War Refugee Board, p. 17.

254. Alfred E. Zollinger, the IRC representative in Washington, transmitted the offer on July 25. For text of the IRC note and of the U.S. reply of August 11, see ibid., pp. 20-22. See also Conway, " Between Apprehension and Indifference," p. 44.

255. PRO, Fo. 371 /42810, pp. 174-175. Linton also had a discussion with Henderson on this issue on August I. Weizmann approached Eden on September 6. For the minutes of the Linton-Henderson meeting and for a copy of Weizmann’s letter, see Weizmann Archives.

256. PRO, Fo. 371 /42810, pp. 200-202. A copy of the minutes of the meeting with the JGC leaders was sent to Washington on July 24. See telegram no. 17024 from John W. Allison of the American Embassy in London to the State Department.

257. Ibid., Fo. 371 /42812, p. 34.

258. Ibid., 371 /42810, p. 57.

259. Ibid., 371 /42 814, pp. 27-28. See also the minutes of the August 4 meeting of the War Cabinet Committee on the Reception and Accommodation of Refugees, ibid., CAB.95 / 15.

260. Ibid., 371 /42814, pp. 69-70.

261. Ibid., pp. 29-30. For a summary of the British position on the Horthy offer, prepared on August 8 for the War Cabinet, see ibid., pp. 74-76.

Questions relating to the Horthy offer were raised a number of times in the House of Commons. On August I, Edmund Harvey and others questioned Dingle Foot, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Economic Warfare; on August 2, Hewlett questioned Eden; and on November 8, Hammersley and Sir T. Moore questioned Eden. Great Britain. House of Commons. Parliamentary Debates (Han sard), 1944: 402, August I, 1944: 1140-41; August 2, 1944: 1410; 404, November 8, 1944: 1380.

262. PRO, Fo. 371 / 42814, p. 31. For a summary of the American position, see Winant’ s August 15, I 944, note and memorandum addressed to Eden. Ibid., 371 /428 I 5, pp. 55-58. See also Summary Report of the Activities of the War Refugee Board, pp. 17-22.

263. Summary Report of the Activities of the War Refugee Board, p. 19.

264. For some details, see Conway, "Between Apprehension and Indifference," pp. 44-46, and Vago, " The British Government a nd the Fate of Hungarian Jewry," pp. 219-222.

265. The Department of State Bulletin, 11 (August 20, 1944)269: 175. For further details on the so-called "Horthy offer," see Bela Vago, "The Horthy Offer. A Missed Opportunity for Rescuing Jews in 1944." In: Contemporary Views of the Holocaust, Randolph L. Braham, ed. (Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing, 1983), pp. 23-45. 266. PRO, Fo. 371 / 42815, pp. 78-79.

267. Ibid., pp. 167-168, and Fo.371 /42816, pp. 148-150.

[Braham, Randolph L. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), pp. 998-1002. Lévai, Jenö. Black Book on the Martyrdom of Hungarian Jewry. (Central European Times Publishing, 1948).]

Institute of Geology, Budapest

Levai 1948 p. 398:

“The rescue of the Jews in hiding was greatly facilitated by the false legitimations produced by some clever groups; in most cases they were brought into circulation unselfishly and without (398) payment being demanded for them. Two groups, who carried on this work on a large scale deserve mention. Generally these actions were started in connection with the resistance movement against the Germans, although others had already existed before the German invasion, whose aim it had been - as an anti-Fascist movement - to hide English, Dutch, French, Belgian and Polish officers and men who had escaped from German prisons and to provide them with material help and personal documents. After the German invasion, partly for political and partly for racial reasons, the rescue of the persecuted became predominant and these groups with their organisation were of the greatest help to the Jewish rescue actions. Without exception the members of these groups were Christians with Left-wing sympathies. One of these groups for instance was led by: Dr. Tibor Szalay, director of the Institute of Geology and his wife, Laszlo Csuros, Rafael Ruppert, Ferenc Korom, Karoly Dobos, a Calvinist minister, Baron Jeno Josika and others. They were greatly assisted in the production of forged documents by "underground" foreigners: Capt. Roy Natush from New Zealand, the British Lieutenant Thomas Clement, Flight-Lieutenant of the R. A. F. Reginald Barratt, Sergeant Tibor Weinstein of the Palestine Regiment, the British Privates Gordon Tasker and R. W. Jones, Gordon Park, and Heburn and the Dutch Lieutenants G. van der Waals and W. Puckel.’’

“A printing shop was organised, where they could print blank registry extracts, passes for factories, exemption certificates etc. etc. The necessary stamps were made by Lieutenants van der Waals and W. Puckel, who literally became masters of their art. They even succeeded in producing such perfect German passes, that persons speaking neither German nor Hungarian got by everywhere without the slightest trouble.’’

So great was the activity of that group, - and so successful - that the British Military Mission in Budapest - after a thorough examination of the facts -, submitted the names of the leaders of the group to His Brittanic Majesty together with a proposal of distinction. Until the promised decorations could arrive, Field marshal Viscount Alexander saw to it that they were issued with following document:

"This certificate is awarded to . . . . , Budapest, as a token of gratitude and appreciation for the help given to the Sailors, Soldiers and Airmen of the British Commonwealth of Nations, which enabled them to escape from, or evade capture by the enemy.

H. R. Alexander.

Field marshal. 1939-1945.

Supreme Allied Commander

Mediterranean Theatre"

Many other secret printing offices and societies were engaged in similar work and quite a large number of Christians handed their own personal documents and those of their families over to Jews in order to effect their escape.’’ (399)

Dr. Tibor Szalay, director of the Institute of Geology and his wife,

Laszlo Csuros

Rafael Ruppert

Ferenc Korom

Karoly Dobos, a Calvinist minister

Baron Jeno Josika

Capt. Roy Natush from New Zealand

British Lieutenant Thomas Clement

Flight-Lieutenant of the R. A. F. Reginald Barratt

Sergeant Tibor Weinstein of the Palestine Regiment

British Privates Gordon Tasker

R. W. Jone

Gordon Park

Heburn

Dutch Lieutenant G. van der Waals

Dutch Lieutenant W. Puckel

[Lévai, Jenö. Black Book on the Martyrdom of Hungarian Jewry. (Central European Times Publishing, 1948 p. 398).]

Zionist Youth

Braham, 1981, pp. 1319-1320:

“The Rescue Activities of the Hehalutz Youth. In contrast to the positions taken by the Central Jewish Council (see Chapter 14) and the Vaada, the members of the young Zionist pioneers (and there were only a few hundred of them) took militant action for the rescuing of Jews. By doing so they were responsible for what were by far the brightest hours in the tragic wartime history of Hungarian Jewry. They never engaged in open combat and they failed to sabotage any of the many rail lines leading to Auschwitz (they did not have this kind of power), but their heroic rescue operations can clearly be classified as acts of resistance.’’ (1319)

“The movement was under the leadership of young Zionists belonging primarily to the Hashomer Hatzair and Dror groups. The dominant role in the movement was played by young Polish and Slovak refugees who came to Hungary in 1942-1944. Among these were Neshka and Zvi Goldfarb of Poland, and Rafi (Friedl) Ben-Shalom and Peretz Revesz of Slovakia. 247 These were soon joined by a number of equally brave young Dr. Gyorgy Wilhelm who distinguished themselves during the underground struggle. Special mention must be made of the heroic activities of David (Gur) Grosz, Sandor (Alexander; Ben Eretz) Grosszmann, Yitzhak (Mimish) Horvath, Jozsef Mayer, Moshe (Alpan) Pil, Moshe Rosenberg, and Efra (Agmon) Teichmann.’’ 248

“With approximately 500 members in Budapest, the leaders of the Hehalutz concentrated their attention on rescuing individuals, mostly their comrades and Zionist sympathizers; they had become convinced that there was no hope for the Jewish masses. 249 The nature and scope of their activities varied with the changing situation. Before the occupation, the Hehalutz was primarily engaged in the rescue and "legalization" of refugees. They provided these refugees with the necessary-mostly Aryan-identification papers, and rescued a number of Jews from Polish, Slovak, and other camps. In this rescue campaign they worked closely with the Vaada, especially its Tiyul section.’’ 250

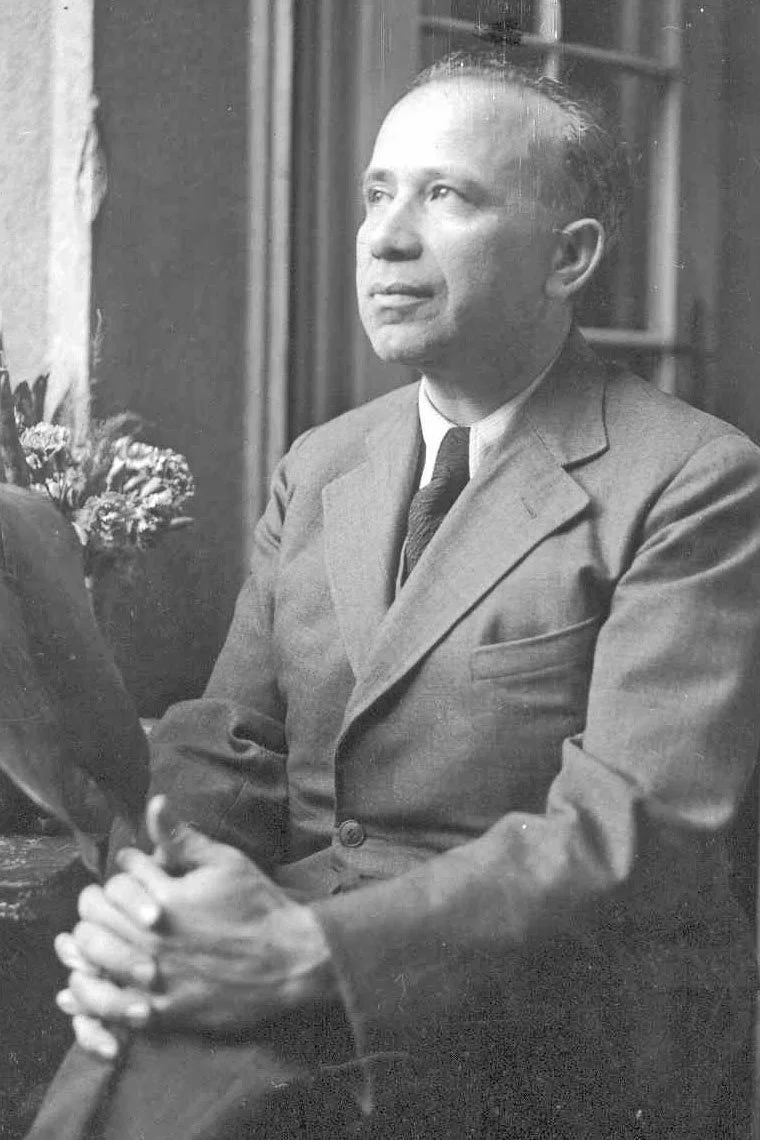

“The German occupation of Hungary caught most of the Halutzim off guard. Their immediate concern was to assure, first and foremost, their own and their families’ safety. Because of the speed with which the anti-Jewish measures had been enacted in the countryside and the weaknesses of the Zionist movement there, the young Halutzim decided to focus on their rescue activities in Budapest. During the first phase of the occupation, the Dr. Gyorgy Wilhelm concentrated its attention on the production and distribution of forged Aryan identification papers-including even Gestapo, SS, and Nyilas membership cards. 253 For reasons of security, the leaders in charge of this aspect of the underground operations, including Dan Zimmermann, Sraga Weil, Grosz, and Teichmann, had to shift their headquarters at great risk to themselves. They naturally never wore the Yellow Star badge, which to their great consternation caused some establishment Jewish leaders to accuse them of trying to extricate themselves from the common lot. Presumably unaware of the ominous implications of the badge, some among the latter were in fact urging their fellow Jews to wear the Yellow Star in proud defiance.’’ 254

“Another important aspect of the Hehalutz work during this period was the organization of small groups of young men and women, mostly followers of one or another Zionist organization, for the smuggling of Jews into Romania and Slovakia, where the anti-Jewish drive at the time was at a standstill. Among those most active in the smuggling of Jews into Romania were As her Aranyi and Hannah Ganz (Grtinfeld), members of Dror-Habonim movement. According to their postwar accounts, they were unable to persuade the establishment leaders of the Jewish (1321) communities they bad contacted in Northern Transylvania about the seriousness of the situation. Nevertheless, they managed to distribute a number of forged documents and smuggle a number of Jews across the Romanian border, including Rabbi Mozes Weinberger, the Chief Rabbi of the small Neolog community of Kolozsvar. 255 A few groups of Jews were also smuggled into Tito's Yugoslavia. After the capture of one of their comrades (Avri Lisszauer), this route was de-emphasized, especially since the Vaada leaders had protested that its use was a threat to their negotiations with the Germans.’’ 256

Notes

247. Zvi Goldfarb, "On ' Hehalutz' Resistance in Hungary." In: Extermination and Resistance (Israel: Kibbutz Lohamei Hagetaot, 1958), I: 162-173. See also his statement of April 1, 1962, in Moreshet, Archives File A. 94. Goldfarb was a leader of the Dror movement. One of his closest associates in the movement was his wife, Neshka, a woman from Munkacs. He died in Kibbutz Parod in January 1978. Ben Shalom, Weil wir Leben wollten (Because We Wanted to Live), 152 pp. Moreshet, Archives File D.2.88. Hebrew edition: Neevaknu le'maan. he'haim (We Struggled for Our Lives) (Givet Haviva: Moreshet, 1977), 223 pp. A leader of the Hehalutz, Ben Shalom came to Budapest in January 1944. A representative of the Hashomer Hatzair movement, he went to Israel in 1947. He later served as Israel’s Ambassador in Mali, Cambodia, and Romania. Revesz, Hashoa be'Hungaria (The Holocaust in Hungary), statement available at the Center for Historical Studies at the University of Haifa, 14 pp.

248. An 18-year-old in 1944, Grosz was particularly active in the printing, storing, and distribution of false papers; he often went about disguised as a Nyilas, in uniform and armed. His account is reproduced in Ben-Shalom’ s Neevaknu le'maan he'haim, pp. 176-205. Mayer, whose underground name was Joska Megyeri, also dressed in Nyilas uniform; he maintained close contact with several non-Jewish resistance groups. For his account see ibid., pp. 149-160. For Pil’s account see YIVO, Archives file 187/3619; for Teichmann's account see Ben-Shalom, Nee vaknu le'maan he'haim, pp. 161-175. See also David Gur, Brothers for Resistance and Rescue. The Underground Zionist Youth Movement in Hungary during World War II. (Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2007), 270 pp.

249. Ben-Shalom, Weil wir leben wollen, pp. 32 and 46.

250. For details on the activities of the Halutz youth in 1942 and 1943, see Asher Cohen, The Halutz Resistance in Hungary, op. cit., pp. 16-52, and A halal arnyekaban. A nagy megprobaltatasok kora (In the Shadow of Death. The Age of Great Challenges). Hava Eichler and Yehuda Talmi, eds. (Tel Aviv: A Hanoar Hacioni Vilagmozgalom kozpontja, 1991), 66 pp., and Haim Genizi and Naomi Blank, "The Rescue Efforts of Bnei Akiva in Hungary During the Holocaust." In: YVS, 23 ( 1993): 73-212.

251. See his Weil wir Leben wollten, pp. 6 and 8. See also Chapter 23. 2

52. Ibid., pp. 24-28.

253. The originals of these documents were usually purchased from Polish refugees who had access to Hungarian officials.

254. According to Ben-Shalom this was also the reaction of some Zionists, including Zvi Szilagyi of the Vaada. See his Weil wir Leben wollten, p. 35.

255. Asher Cohen, The Halutz Resistance in Hungary, op. cit., pp. 76 and 91-93. Ganz’s closest collaborator in Kolozsvar was Yehuda (Pici) Levi. Ganz was apprehended in Kolozsvar and deported to Auschwitz, but survived to tell her tale. For further details on the Romanian rescue operations of the Halutz youth, see the testimonies of Hannah Ganz, Eszter Goro-Frankel, Asher Aranyi, and Arieh Hirsch (Eldar) at the Center for Historical Documentation at Haifa University.

256. Ben-Shalom, Weil wir leben wollten, p. 45.

Levai, 1948 p. 388-391

“Here it must be mentioned how the Zionist Youth Movement played a most active part in the rescue actions. Clad in various illegally worn uniforms and equipped with false legitimations, groups of young Zionists nightly patrolled the streets, wearing Nyilas armlets or disguised as members of the National Guard. Often enough they accosted real Nyilas members, asked to see their documents and declared. them to be false, whereupon they confiscated them. These authentic passes and legitimations they then used for further rescue actions’’.

“Another group of youths, consisting of both Zionists and non-Zionists, settled down in the rescue department of the International Red Cross and tried-by legal and mostly by illegal means-to rescue as many people as possible from the brick-works. This group even succeeded in establishing contact with Laszlo Ferenczy, whom they induced to grant favours by making Red Cross parcels available to him. With the authorisation of the Rescue Department of the International Red Cross, Mrs. Breuer and Vera Gorog put in a daily telephone call to Capt. Lulay, Ferenczy's deputy. In order to avoid attracting attention the code-word "Cousin Veronica called her Uncle Laci" was agreed upon, and most valuable information together with the documents required for the rescue work were obtained.’’

“Wearing an armlet describing him as "Delegate of the International Red Cross" Dr. Pal Szappanos, accompanied by Dr. Laszlo Benedek in the guise of a "Christian doctor," took turns with various other Jewish doctors (Dr. Laszlo Tauber, Dr. Glancz, Dr. Nemet and others) in paying daily calls to Teleki Square in order to liberate Jews from deportation under the pretext of "illness."

“The inventiveness of the Jewish Youth was inexhaustible and many Jews owe their lives to that animated body of men.’’

“At this time atrocities were again occurring and Locsey issued new blue legitimations; from that time on all Christians entering the ghetto had to be in possession of these blue legitimations. At the same time-on instructions of Solymossy-he gave orders to form mixed guards (police and Nyilas) in and around the ghetto. This led to a reduction in the number of atrocities committed, although looting under the pretext of "looking for arms" took place at 10, Rumbach Sebestyen Street, 5, Klauzal Square, 30, Klauzal Square etc.’’ (390)

“The Jews were provided with green legitimations, which enabled them to leave the ghetto. In case an operation proved to be urgently necessary, they could go to the hospital in 44, Wesselenyi Street by producing a white legitimation provided by the Council; on the other hand groups could go to the hospital escorted by police.’’

Mrs. Breuer, Rescue Department of the International Red Cross

Neshka Goldfarb, Poland

Zvi Goldfarb, Poland

Vera Gorog, Rescue Department of the International Red Cross

Sandor (Alexander; Ben Eretz) Grosszmann, Swiss building at 17 Wekerle Sandor Street

David (Gur) Grosz

Lajos Gottesman, Betar, Provincial Department (Videki Osztaly) of Jewish the Council

Yitzhak (Mimish) Horvath

Jeno Kolb, Jewish Council's Information Section

Jozsef Mayer

Moshe (Alpan) Pil

Peretz Revesz, Slovakia

Moshe Rosenberg, Hashomer Hatzair

Rafi (Friedl) Ben-Shalom, Slovakia

Efra (Agmon) Teichmann.

Sraga Weil

Dr. Pal Szappanos, Rescue Department of the International Red Cross

Yehuda Weisz, Jewish Council's Information Section

Dr. Gyorgy Wilhelm

Dan Zimmermann

[Braham, 1981 pp. 1319-1320; Lévai, Jenö. Black Book on the Martyrdom of Hungarian Jewry Central European Times Publishing, 1948, pp. 388-391]

Clothes-Collecting Company (Ruhagyujto Munkasszazad), known as Section T of the International Red Cross

Braham 1981:

“Labor servicemen were involved in other forms of resistance as well. A unit of 25 men from Company No. 101/359, the so-called Clothes-Collecting Company (Ruhagyujto Munkasszazad), for example, provided special services to the persecuted Jews. Known as Section T of the International Red Cross, this unit, led by Dr. Gyorgy Wilhelm, the son of Karoly Wilhelm, engaged in many heroic rescue operations. The men of this unit, including Istvan Bekeffi, Istvan Komlos, Istvan Radi, and Adorjan Stella, rescued Jews from the death marches to Hegyeshalom and supplied the food made available by the International Red Cross to the children’ s homes and the ghetto. Ironically, they too had to be rescued on November 29, when they were scheduled for entrainment and deportation. This was achieved through the efforts of a rescue group headed by Sandor Gyorgy Ujvary, a journalist of Jewish background, who was associated with the International Red Cross and the Papal Nuncio. 246 The rescue activities of Section T, like those of the Ujvary group, paralleled those undertaken by the Halutzim.

Notes

246. Levai, Szurke konyv, pp. 200, 203-206. For further details on Section T, see Chapters 10 and 31; on Ujvary's activities, see section "The Vatican and the Budapest Nunciature " in Chapter 31.

Dr Gyorgy Wilhelm, Head

Istvan Bekeffi

Istvan Komlos

Istvan Radi

Adorjan Stella

[Braham 1981; Lévai, Jenö. Black Book on the Martyrdom of Hungarian Jewry Central European Times Publishing, 1948.]

The International Red Cross

Braham, 1981, pp. 1401-1409:

“Until the middle of July 1944 the International Red Cross (IRC) 1 was not directly involved in the protection of the rights and interests of Jews per se. In Hungary, as elsewhere, the IRC scrupulously adhered to the letter and spirit of the 1929 Geneva Convention, which restricted its activities primarily to matters relating to prisoners of war. It preferred not to get involved with matters involving civil populations at large-the primary concern of the national Red Cross organizations-let alone with the defense and protection of minority groups against abuses by their own governments.’’

“The IRC was not inclined to accept the suggestion of Jewish organizations, spearheaded by the World Jewish Congress, that it confer upon the Jews held in the ghettos and the labor and concentration camps the status of civilian interne es-a procedure that would have enabled the IRC to carry out local inspection visits, send food parcels, provide medical care, and in the process perhaps save hundreds of thousands of lives. Aryeh Tartakower and Aryeh L. Kubowitzki (later Kubovy) of the World Jewish Congress suggested this to Dr. Mark Peter, the IRC's representative in the United States, in a sharply worded letter of December 10, 1943. This was followed by a personal discussion on January 5, 1944. Unfortunately, the IRC failed to approach the German Foreign Office with the demand that it confer the status of civilian POWs on all foreigners detained in Germany and the occupied countries until October 2, 1944, when the collapse of the Third Reich was already evident to almost everybody.’’ 2

“There were several reasons for the IRC’s reluctance to get involved in the rescue of Jews. For one thing, the Germans had declared that the Jews were not internees but detainees-a penal rather than a civil category. Consequently the supervision the IRC was empowered to exercise over the treatment of prisoners and internees did not apply to them. The IRC also claimed that continued protests in support of the Jews would be resented by the authorities and prove detrimental to the Jews as well as to other fields of IRC activities. 3 The IRC summarized its position as follows:

‘If help for the Jews had been the only cause which the international Committee was called upon to serve during the war, such a course, (1403) which could have put honor before the saving of life, might have been contemplated. But such was not the case. Relief for Jews, like relief for deportees, rested on no juridical basis. No convention provided for it, nor gave the International Committee even the shadow of a pretext for intervention. On the contrary, conditions were all against such an undertaking. Chances of success depended entirely on the consent of the Powers concerned. And there were all the other tasks, which the Conventions or time-honored tradition permitted the International Committee to undertake, or which, with so great difficulty, it had succeeded in adding thereto. To engage in controversy about the Jewish question would have imperiled all this work, without saving a single Jew.’’ 4

“Following this line of reasoning, the attitude of the IRC delegation in Hungary was at first identical with that manifested elsewhere in the world. The delegation restricted its activities to its traditional functions: responding to inquiries by foreigners and monitoring the treatment of prisoners of war, to whom it also forwarded parcels. These included thousands of Polish and Yugoslav prisoners and a smaller number of other Allied prisoners of war.’’ 5

“The IRC had been aware of the mass expulsion and subsequent massacre of the "alien" Jews of Hungary in the summer of 1941, and even discussed the " incident" in December without taking any action. By the summer of 1942, it had fully known that the Nazis were systematically massacring the Jews of Europe. Nevertheless, it continued to remain silent for fear of confronting the Germans. 6 Until October 1943, it even refused to send a delegate to Hungary despite repeated requests by the international Jewish organizations. The many reports and suggestions of Jean de Bavier, IRC’s first delegate in Hungary, calling for the alleviation of the plight of the suffering Jews and for the forestalling of a looming greater disaster, were not given any serious consideration at headquarters.’’

“On February 18, 1944, de Bavier, seeing the portents of the German occupation of Hungary, asked Geneva for instructions on how to save Hungarian Jewry from the fate that bad befallen the Jews of Poland and other Nazi-occupied countries. On March 27, i.e., a few days after the occupation, de Bavier suggested that Max Huber, the president of the IRC, go and see Hitler with a view to improving the (1404) plight of the Jews of Hungary. 7 The failure of the IRC to follow up on de Bavier' s suggestion was characterized by Aryeh Ben-Tov, an authority on the activities of the IRC during the Second World War, as one of its greatest failures.’’ He concluded:

‘Since the institution did not act in Hungary during the crucial months of the deportations and did not make the facts known either to enough interested organizations or to a sufficiently wide audience in general, the SS and the Hungarian Fascists were able to go much further than would otherwise have been possible in their attempts to implement the Final Solution.’ 8

“De Bavier was recalled to Geneva, reportedly because he did not speak German, and replaced by Friedrich (Fritz) Born, the director of the Swiss-Hungarian Chamber of Commerce of Budapest (A Budapesti Svaj ci-Magyar Keres kedelmi Kamara).9 Although Born assumed his duties on May 10, after the ghettoization in the provinces was coming to an end, the IRC continued to maintain the same posture of neutrality that had characterized its earlier position. A change in its attitude came about only after the Swiss press published some gruesome accounts on the Final Solution in Hungary based on materials forwarded to Switzerland on June 19 by Miklos (Moshe) Krausz, the bead of the Budapest Palestine Office (Chapter 23). About two weeks after the late June interventions by President Roosevelt, the King of Sweden, and the Pope, the IRC also decided to play a more active role in Hungary. The organization’s visibility became higher in both Budapest and Geneva. Born began a more active campaign, visiting the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other agencies on behalf of the deportees. He also contacted Theodor Horst Grell, the specialist in Jewish affairs in the German legation, who had assured him that the Hungarian Jews were being taken to Germany only to work and that since the Germans needed able-bodied and healthy Jews they, the Germans, bad themselves berated the Hungarians for occasional mistreatments. Moreover, Grell had also assured Born that once the Jews arrived in Germany they were well taken care of and physically strengthened before assignment for labor. He rejected the suggestion that the IRC visit some of the camps. These camps, he argued, were spread throughout Germany and Poland (1405) and since the Jews were engaged in the production of war materiel, their location had to be kept secret.’’ 10

“On July 7, the day after Horthy had halted the deportations, Max Huber approached the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He wanted all available information that would ease the worldwide restlessness over the alleged events in Hungary, as well as permission for an IRC delegate to visit some of the ghettos and entrainment centers in which Jews were interned and distribute food and clothing. 11 A more specific request was submitted by Imre Tahy, the Hungarian charge d’affaires in Bern, on July 19. Reporting on a meeting he bad a day earlier with Carl J. Burckhardt of the IRC, Tahy urged that Hungary request the Germans to allow Dr. Robert Schirmer, the IRC delegate in Berlin, to visit Budapest. He emphasized that Schirmer bad been asked to deliver a message to Horthy in connection with the Jewish question.’’ 12

“Schirmer arrived in Budapest shortly thereafter, and on July 21 be met with Sztojay. Schirmer repeated the request that was earlier submitted by Huber. He suggested that he be allowed to visit some Yellow-Star houses; that the "shipment of Jews for labor abroad" cease and Jews be concentrated instead in ghettos similar to the one that was established in Theresienstadt, which an IRC delegation had visited and approved of on July 23; 13 and that the IRC be given an opportunity to investigate the fate of the British and American pilots who were shot down over Hungary.’’ 14

“The response of Sztojay and Andor Jaross was transmitted to Schirmer on July 23 by Denes Csopey, the head of the Political Department of the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The two leaders concurred with Schirmer's requests and suggested that the IRC delegation visit the Kistarcsa and Sarvar internment camps, which also contained non-Jewish political prisoners, and that the planned visits to Yellow-Star houses were to be undertaken in consultation with Jozsef Szentrniklossy, the bead of the social-political division in the mayor’s office. 15 On July 27 and 28, a Schirmer-led IRC delegation visited the Kistarcsa and Sarvar camps, which were under the respective command of two decent men, Istvan Vasdenyei and Gyorgy Gribowszki. The situation in the camps was found to be quite acceptable. It is safe to assume that by then the delegates had been aware that the Germans bad managed to deport approximately 1,300 Jews from Kistarcsa and (1406) around 1,500 Jews from Sarvar a short while before the visit in spite of Horthy's halting of the deportations and the assurances given to the IRC. 16 The delegation also visited a few carefully selected Yellow-Star houses and Jewish institutions, finding the conditions generally satisfactory, although overcrowded. 17 The visits, presumably, gave a false picture of the dire situation Hungarian Jewry had lived under. Just as the IRC’s visit to Theresienstadt on June 23 had not revealed the realities of Auschwitz and Treblinka, the visit to the Kistarcsa and the Sarvar internment camps could, clearly, not disclose the horrible conditions that prevailed in the many brickyards and entrainment centers, let alone in the ultimate destination following their deportation.’’

“While in Budapest, Schirmer also approached Edmund Veesenmayer, the Reich’ s Plenipotentiary in Hungary, requesting permission to send packages to the deportees, to visit the camps, and to accompany the inmates on a deportation train to Kassa. Veesenmayer, after consulting with Eichmann, sent a telegram to the German Foreign Office (August 2), in which he said be would be ready to approve the first two requests " if adequate preparations were made." However, be urged that the last one be rejected, asserting that "this would violate the secrecy related to the travel route and destination." Adolf Hezinger, the Foreign Office’s expert on the treatment of Jews of foreign citizenship, was given responsibility for the reply. In a note to Horst Wagner, the head of Inland 11, he suggested the same answer that Hitler had given on July 10 to the Hungarians in connection with their earlier request to permit the emigration of some Jews. (This was in response to the appeals of Sweden, Switzerland, and the American War Refugee Board-see Chapter 25.) Hezinger suggested that the distribution of packages was to be allowed " only after the resumption of the transfer of Jews into the Reich. " He rejected the idea of anyone accompanying a deportation train, but hedged on the possibility of a camp visit "after thorough preparatory work in cooperation with Eichmann." 18

“The IRC confidentially informed the local and international Jewish organizations in Switzerland about its activities. On July 21, Burckhardt met with the leaders of a few Swiss Jewish organizations; this was followed by a larger meeting on August 10 that was attended by Huber and representatives of the 17 largest domestic and international organizations and agencies in Switzerland, including the World Jewish (1407) Congress, the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the Palestine Office, and the AJDC. Burckhardt reviewed the situation of the Jews in Hungary, emphasizing the activities the IRC had undertaken on their behalf. One of the objectives of the meeting was to impress upon the leaders of the local and international Jewish organizations the need to coordinate their activities. 19 Although the conferences, like the notes and memoranda handed to Jewish organizations, were identified as confidential, the Germans became privy to their contents. (The Germans frequently intercepted the mail and the memoranda that the Jewish leaders in Switzerland forwarded to their counterparts in Istanbul or Palestine. 20)’’

“While the IRC never achieved the goals it had outlined for Veesenmayer in July, in August it did become more involved in two plans of great interest to the Jewish community: support of the Spanish, Swiss, and Swedish-initiated emigration schemes and the protection of children. On July 12, the Central Jewish Council had been informed that Spain was ready to accept 500 children. On the advice of Angel Sanz-Briz, the Spanish charge d'affaires in Budapest, the Council persuaded the IRC to take the foreign-protected children under its aegis. The IRC, which consented to the suggestion early in August, thus acquired a legal framework by which to expand its activities to include the protection of "foreign "civilians.’’

“The Spanish offer induced Burckhardt on August 9 to approach Baron Karoly Bothmer, the bead of the Hungarian Legation in Bern. He suggested that Hans Bachmann, the IRC secretary-general, meet Tahy, who had earlier assured the IRC that Hungarian Jews holding Palestine immigration certificates or visas from neutral states would have the right to leave the country. The Hungarian response, formulated by Csopey on August 26, asserted that the Hungarian government would recognize the competence of the IRC in all aid and immigration matters which it represented or initiated with the Hungarian government. The IRC took full advantage of this position statement and intervened a number of times, urging the Hungarian government to speed up the emigration of 2,000 Jews, which was being processed by the Swiss Legation in Budapest. 21 It also transmitted the notes of the Allied governments to the same effect. On August 16, for example, the British and American governments informed the Hungarians that they had accepted Hungary’s earlier offer (see Chapter 25) and would " make arrangements for the care of such (1408) Jews leaving Hungary who reach neutral or United Nations territory. " 22 Though such efforts continued until the Soviet forces liberated Budapest, no groups were ever permitted to leave Hungary as a consequence.’’

“By far the most important contributions of the IRC to the Jewish community in Budapest were the sheltering of children and the safeguarding and supplying of Jewish institutions, including the ghetto, during the Nyilas era. Plans for the protection of children were laid in August in light of the lingering threat of deportation, the continual dwindling of communal supplies, and the dangers associated with the rapidly approaching front.’’ 23

“Under Born's leadership two sections dealing with children were established within the framework of the IRC: Section A, which was placed under the leadership of Otto Komoly, the Zionist leader, 24 and Section B, which was entrusted to Reverend Gabor Sztehlo of the Good Shepherd Committee. 25 In addition, Born had been responsible for the establishment of Section T (Transportgruppe; Transportation Unit), which was composed of 25 to 35 recruits of Labor Service Company No. 101/359, the so-called Clothes-Collecting Labor Company (Ruhagyujto Munkasszazad), which was under the command of Captain Laszlo Ocskay. Section T, which was headed by. Dr. Gyorgy Wilhelm, the son of Karoly Wilhelm of the Central Jewish Council, and Istvan Komlos, was engaged in relief, rescue, and resistance operations. It was particularly active in the rescuing thousands of Jews from the death-marches to Hegyeshalom and in supplying the children’ s homes and the ghetto with food and fuel.’’ 26

“During the Nyilas era, the IRC took under its protection a large number of Jewish and non-Jewish institutions-hospitals, public kitchens, homes for the handicapped and the aged, research and scientific institutes, and various shops. 27 Each of these institutions was identified by a plate posted at the main entrance that read: "Under the Protection of the International Committee of the Red Cross" in Hungarian, German, French, and Russian. Born and his associates kept track of the anti-Jewish measures of the Nyilas, including those officially initiated by the government and those that were illegally perpetrated, and appeared frequently before the leaders, especially Baron Gabor Kemeny, the Foreign Minister, to help alleviate the plight of the Jews. It was thanks to these interventions that on October 30 the government (1409) announced the recognition of the protective passes issued by the Vatican and the foreign legations as well as the granting of ex territorial status to all institutions and buildings protected by the IRC.’’ 28

“Shortly after the Budapest ghetto was established, Hans Weyermann arrived from Geneva to assist Born. Though the relationship between the two IRC representatives was not the most harmonious one, they managed to divide their responsibilities during the critical weeks before the capital's liberation. Before the Soviet siege of Budapest began on Christmas Day, 1944. Born withdrew to his home in Buda from where he directed the activities of the IRC in that part of the capital. Weyermann’ s responsibilities were concentrated in the Pest part, where the ghetto was located. The effectiveness of the IRC during this time was greatly enhanced by its cooperation with the Papal Nuncio and of the representatives of the neutral states. In fact, some of the measures that were adopted in support of the beleaguered Jewish community, including the protection of the children's homes and the rescuing of Jews from the death marches, were conceived and carried out jointly (see below).’’ 29

Notes

1. The International Red Cross is frequently referred to as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

2. Aryeh L. Kubovy, "The Silence of Pope Pius XII and the Beginnings of the ' Jewish Document '." In: YVS, 6: 7-11. See also Unity in Dispersion (New York: World Jewish Congress, 1948), pp. 167-169.

3. Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on Its Activities during the Second World War (Geneva, 1948), I: 641. For a well-documented account of the efforts of Gerhart M. Riegner and other leaders of the World Jewish Congress, often acting in cooperation with Jaromir Kopecky, the delegate of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile in Switzerland, to induce the IRC to act on behalf of the oppressed Jews, see Monty Noam Penkower, The World Jewish Congress Confronts the international Red Cross during the Holocaust. Jewish Social Studies, New York, 41 (Summer-Fall 1979)3-4: 229-256. 4. Inter Arma Caritas (Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross, 194 7), p. 76.